England, France and Germany saw war as a glorious engagement. The prevailing thought by those who joined the military was that they would be home by Christmas. Young men were bored with the good quality of life so were eager to prove themselves and their new sense of national identity. Because of advancements in technology (machine guns, tanks, large guns, airplane) and changes in fighting (trench warfare, volunteer army rather than conscripts) the war lasted much, much longer and was much more devastating than planned. As secularism replaced religion, war was the natural or scientific way to show nationalism and patriotism.

There is much contention, at least among German historians, about numerous points leading up to the First World War. For German historians, the issues stem around the internal or external focus of the Wilhelmine government, the relative versus the actual influence and power of the lower classes over the ruling elite, and when Germany first made a decision to go to war, and the contentions surrounding German preparations for war. Volker Berghahn provides an excellent discussion on the historiography of Germany leading up to World War I. Refuting any attempts at placing a Sonderweg to Nazi Germany, Berghahn argues that Germany did not face different paths than other European countries, they just made different choices. In other words, Germans faced the same choices, they just reacted differently than other countries. Berghahn shows how internal pressures from an “unstable” government (a rise in the Social Democratic party demanding more power in the Reichstag for the lower classes and an obdurate ruling elite unwilling to give up power) and external pressures from countries who sought to keep Germany restrained, eventually left German leaders feeling they had no other alternative than to create what they hoped would be a small internal war that would unify and subdue German speaking areas politically, and provide breathing room for lack of ability to colonize off continent. German leaders felt they were not able to decide if a war would happen, so they chose to decide when it would happen.

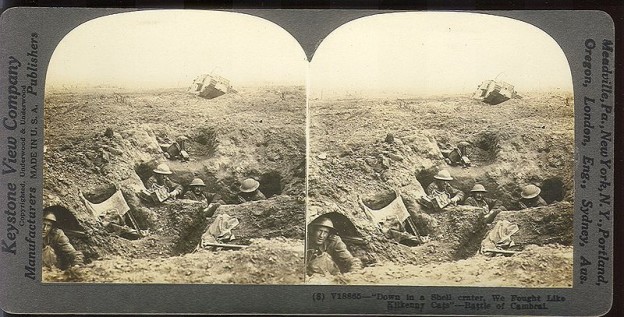

The war that followed came as a shock to all participants. Everything came in greater and staggering numbers. Loss of life in a single battle was immense compared to previous wars. The war left a lasting and different impression on each nation. War afflicted nearly half of all men in France, and turned them into ultra pacifists. Their desire to refrain from all future conflict led directly to complicit attitudes towards the future Nazi party. Germans felt stabbed in the back and let resentment and unfair reparations requirements foster in their culture. Forced to employ a democratic government and divert a great percentage of their economy to their enemies, Germany plunged much deeper into economic depression and hyper inflation than other countries of the world that experience the Great Depression. Germans became more politically militant instead of democratic, and were left pining for the “Golden Days” before the war.

And the British… I haven’t read about them past 1914.

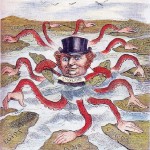

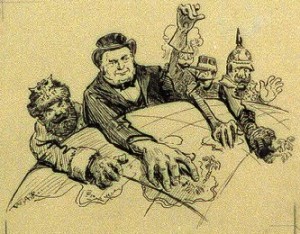

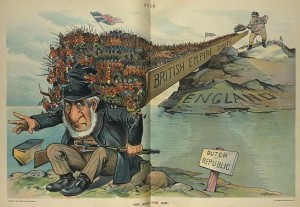

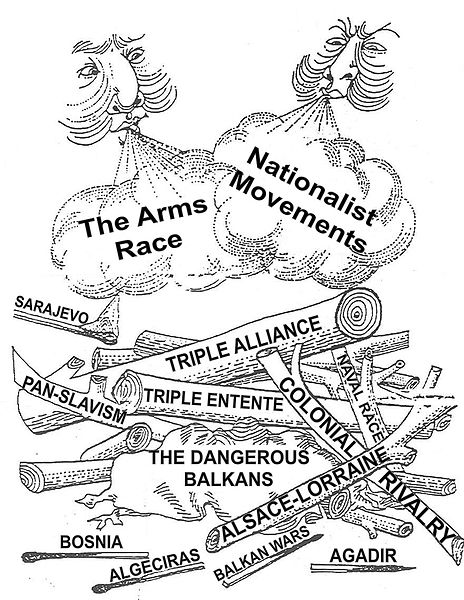

Take a look at the picture below, drawn by Harris Morgan and submitted to wikimedia.org. I think it sums up nicely the different factors that led to the First World War. Perhaps one of the logs should be labeled “German political discord”. All of these external factors, plus the internal pressure of political change, fanned by the euphoric ideals of nationalism and trying to beat someone else (the arms race), led to a very uncivil expression of emotion.

Work Cited:

- Volker Rolf Berghahn, Germany and the Approach of War in 1914, 2nd ed. (New York, N.Y: St. Martin’s Press, 1993).