Modernization is the term used to describe the process of how a society was before, compared to how it is now. It most often encompasses development and use of mechanical technology, a change in gender roles, a real or perceived rise in standard of living, adjustments in social classes, and, often, political change. Modernization at times was seen in different ways including: a detriment to human society, a marvelous improvement to society, an effect of economic and political challenges, and, most recently, as an inevitable evolution of progress.

Modernization is the term used to describe the process of how a society was before, compared to how it is now. It most often encompasses development and use of mechanical technology, a change in gender roles, a real or perceived rise in standard of living, adjustments in social classes, and, often, political change. Modernization at times was seen in different ways including: a detriment to human society, a marvelous improvement to society, an effect of economic and political challenges, and, most recently, as an inevitable evolution of progress.

Modernism in England can be seen in all these ways in the nineteenth century. The Industrial Revolution, as pointed out by E. P. Thompson had a great impact on the social and economic status of the poor as whole industries turned to machines in factories and entire occupations (think weavers) were discontinued. Formation of factory unions lead to a politically emboldened populace. The Victorian period is known for the ideals of separate spheres for men (political, public, and occupational) and women (private, nurturing) that are still observed and discussed and contested to this day. As Robert Wohl writes, these Victorian ideals are what caused many young individuals (in England, France and Germany) during the turn of the century to question the role of authority and the place of such ideals. English technological modernism during the 19th century was hampered by the desire of the business classes to emulate the aristocracy. Martin Wiener writes that this English pastoralism affected the economy by not allowing it to grow as in other countries. Another form of modernist government was seen in England as Parliament enacted many laws that directly interfered with individuals. Laws governing the poor, woman’s rights, education, and voting abilities all showed, for better or worse, a government with more interest in their citizens.

If modernization is characterized primarily by use of technology, especially of an industrial revolution, then Germany got off to a late start comparatively. But following the unification and industrialization in late 19th Century, Germany showed great progress. Advances in aviation with Zeppelin, in art with the Bauhaus movement are just two of the many examples. Politically Germany changed from a group of loosely connected principalities to become a federated nation with, albeit very weak, parliamentary government. At the turn of the century, German youth were struggling with the sense of modernism and formed many youth groups to express concern with political and social issues. Germany showed a peculiar sense of modernization during the Third Reich. Whereas Nazi ideology extolled the life of the peasant, the simple life of the Volk, seemingly anti-modern, they still exhibited very modern practices. The building of the Autobahns, the development of the first ballistic missile, the successful flights of the first jet powered aircraft were all seemingly contradictory to basic Nazi ideology.

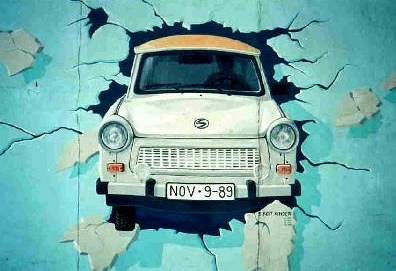

During the bifurcation years, West Germany enjoyed the status of a technologically advanced and modern country. East Germany suffered the stigma of a backwards and inept Soviet satellite country, incapable of keeping up with modern technologies. Stokes shows, though, that East Germany maintained technical competence through the length of its existence (longer than the Third Reich, Weimar Republic and Imperialism, a testament to a successful country with successful technologies such as the Trabant, optics, and computers. What didn’t work in East Germany was the political desire to keep up with western technology, but the ineptness at maintaining a supportive economy, due in part to Soviet inability or unwillingness to support East German technologies. East Germany, in effect, sought to specialize in the fringe technologies of the west, but did not have the underlying infrastructure to support them.

Modernization in the political sense has been attributed to the French Revolution. Changes between monarchies (and empires) to republics throughout the early 19th century sparked the social and political movements in Europe towards self-governed people (something which the nobility and educated classes thought undesirable and potentially devastating). As the Second Empire moved into the Third Republic, self-government began in earnest, as national governments allowed local governments more control. National governments also became more interested in the individual citizens, much the same as in England, as they enacted laws restricting religion and regulating education. As always a factor, the Dreyfus Affair showed a nation struggling with the society and the ideals that came out of political change. Continual losses (Franco-Prussian, WWI and WWII) to Germany and colonial troubles led France to desperately look towards modern technology, such as nuclear power, to regain international standing, and create a positive national narrative.

Works Cited:

- Raymond G Stokes, Constructing Socialism: Technology and Change in East Germany 1945-1990 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

- E. P Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Pantheon Books, 1964).

- Robert Wohl, The Generation of 1914 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1979).