So, I finally get to teach a college course this semester. Way excited! But I refuse to do the normal lecture format. Seriously, we are still stuck on that teaching method after all the research and scholarship about the best ways to teach? (These all came up as results for searching in Google Scholar with the terms “how students learn” and “scholarship of teaching and learning”, which returned over 3.7 million results.)

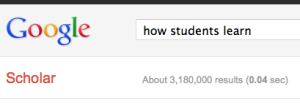

I still believe the “learning pyramid” has merit despite it’s obvious over-generalizations and fabricated percentages. Lecturing has it’s place, but not in my class room. If anything, I want to be less boring. 🙂

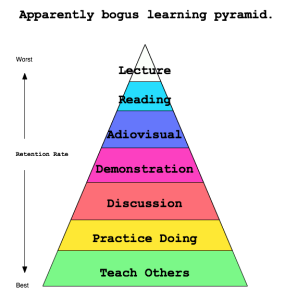

So, I got to thinking, what format do I want to use for my Monday-Wednesday-Friday, History 100 Western Civilization class? I landed on a discussion based lecture format for Monday and Wednesday, and what I’m calling a History Lab for Friday. The sciences have this same format. Lecture on two days a week, then go to a lab where you practice what was preached. I figured we could do the same thing with critical thinking skills taught by the humanities. Monday and Wednesday will be a bit of me talking about the time period, with a healthy dose of questions and comments from the students based on the reading they have done. Then on Friday we have a History Lab where we critically examine a primary document from the time period we are learning about. I’m open to other ideas on what to do during the History Lab. I’m excited to see if any students offer suggestions.

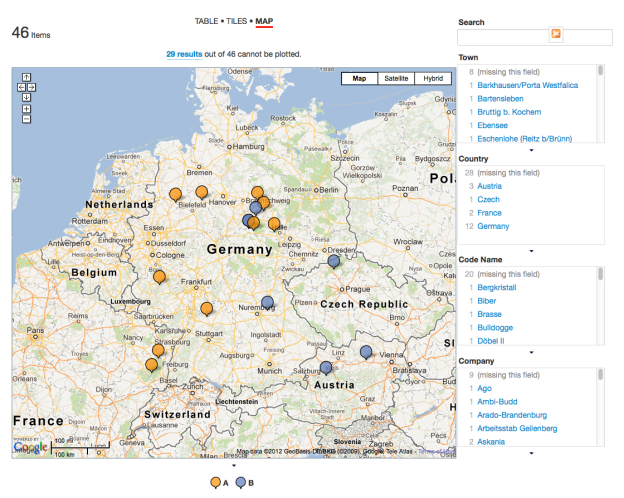

Today was our first History Lab, and it went very well, I think. I will get the students opinion on Monday, to make this exercise an all around learning experience. For today’s History Lab I divided the students into groups of five (any more than that gets a bit unmanageable). They each picked a popsicle stick I had in a cup at the front of the desk. There were five popsicle sticks with the same color, but a different “filter” written on each of the five sticks. The filters are the biases, or lenses through which to look at history. They included race, gender, science/technology, social class, art, religion, and politics/government. After the students organize into groups, I give them a primary source document to read together, then discuss the document based on the filter that they have. After enough time to allow individual groups to discuss, we discuss altogether as a class. To track participation, attendance and provide accountability, each group had to write a summary of their discussion on the back of the paper, including their names and which filter they had, to be turned in at the end of class.

This seemed to work out pretty well, and the students had great comments. We looked at “The Spartan Creed”, a poem written by Tyrtaeus in the 7th Century B.C. (unfortunately no reliable source found, just this post in a forum). The most noticeable thing about this document is how heavily male centric it is. Granted, it’s a man writing about war, but there is absolutely no mention of a female. It can be implied by the use of the word “children”, but no fighting for the protection of wife and family, just city and children. Here are some of the comments the students made on their papers for a few of the filters.

Gender: Men are dominant, only men are warriors. No reference to women. The society was very male dominated. Women had no role in the Spartan military, so the code is less relevant to them. Females are not even mentioned in the creed, so men are obviously the dominant gender. Among the men, they are expected to be strong, courageous, honorable, every trait that makes them a mighty soldier, a protector of their city-state.

Art: War is their art, the structure of their army, how they fought, etc. It doesn’t specifically say anything about art, but the way this is written is a form of art and the way the author makes out a man to be is like a piece of art.

Religion: War was treated as a religion. Soldiers were treated as gods when they returned. In death, a Spartan man becomes immortal as his memory is honored as if he is a god. To understand this one must know that in his life he was worshiped for being a good fighter and so that is carried over in a glorious death. Religion and personal values seem to all be related to war; gods are mentioned but the creed is centered around the personal honor of a warrior.

I was pleased with the results. All of the students were engaged in the group work and came up with something intelligent to write about. The beauty of this model is that each student has a focused purpose to look at a historical document, and then is held accountable for sharing something.

Do you have ideas for what we can do in our History Lab? Leave a comment below, and I’ll give it a try!

[Post image from Wikimedia Commons: Glass containers, experimental magnifiers and chemical or alchemy paraphernalia in the Lavoisier Lab 1775 by Jorge Royan. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Munich_-_Deutsches_Museum_-_07-9631.jpg]