I presented the following at the Association of American Geographers Annual meeting on April 21, 2015. I titled the presentation, “Placing Space in the Experiences of Forced Laborers at Porta Westfalica”

What follows is the paper with the images I used in the presentation. This will turn into the presentation I’ll give in Porta Westfalica on May 8, and a journal article this summer, and eventually a chapter of the dissertation.

==========

Location is important for human interaction and growth development. Being able to place ourselves in a location and being able to recall the location of things and events is also critical for our ability to remember. As one psychologist put it, “memory for location is a fundamental aspect of human functioning. Without the ability to remember locations, children and adults would be unable to carry out even basic tasks, such as getting ready for school or preparing a meal.”[1] Indeed, it seems the visual aspect of remembering is integral for recalling memories made with sight. Studies have shown that a person’s memories are affected when they lose their vision, eventually leading to losing memories, “even well-rehearsed and well-consolidated childhood memories, are lost because the relevant visual information, which is a key part of the memory information, is lost.”[2] When vision is lost, the memories made with that vision erode until they are forgotten completely. New memories can and are made, but without the visual component.

Events and experiences are more accurately remembered, and remembered with more detail, when influenced by strong emotional stimulations (such as during traumatic and stressful events). More so, such memories are strengthened by and even depend upon the visual component. During highly traumatic or stressful events the visual awareness is sharpened, hence ones surroundings, ones location and spatial awareness, become more important. Remembering the place helps us remember the event. This is arguably the case for why many holocaust survivors recall so vividly, and invariably include in their autobiographical accounts, the place names of where traumatic events happened.

Often, survivors put great emphasis on recalling with the place where seemingly unimportant events happened, like which town they travelled through on the way to a prison camp. Zsuzsa Farago a 24 year old female Jew from Hungary, for example, could not remember the date when she left Auschwitz for a labor camp, but she did remember several details about the location. “I don’t remember exactly anymore, I believe that we were transferred sometime in the Fall. We were taken to Reichenbach. There was a telephone factory there. I believe that belongs to Czechoslovakia today, then there were Germans. Far away from the city there was a camp, and that’s where we were. And we worked in the factory there.” Specific time aspects seem to fade quicker than spatial aspects of memories.

At other times, the survivor’s grasp of the time was just as acute as their location. Eva Gescheid, a 20 year old female Jew from Hungary, described her journey to Auschwitz and later to Porta Westfalica with such detail. “We travelled for four days and nights, unspeakable suffering, because there were 70-80 people transported in closed cattle-cars. There was absolutely no water. After four days we came to Auschwitz… It was March, rain and snow showers raged. We possessed only one blanket each, which provided only a little protection. Six days and nights we traveled and suffered the torments of hell. Finally we reached Porta. We were unloaded and again left without food; this for two whole days.”

Before I even had the data, I wanted to do some kind of spatial analysis. That’s like buying a car just for the experience of changing a tire, or more accurately, putting the proverbial cart before the horse. Nevertheless, I was certain that there was some spatial context to analyze, for everything happens somewhere, and looking at the somewhere can help us understand more about the events. I also had a tendency to focus too much on the tools and methodology, so it was important to remember that the spatial plotting tools and the data points were not the analysis, but only tools used to analyze.

The first step in gathering data was to determine the scope. With hopes of finding plentiful events, the scope was narrowed to focus only on the time that a survivor was encamped at one of the Porta Westfalica labor camps, Barkhausen, Lerbeck or Hausberge, and their accompanying work site. As I began to assemble the data, looking at the interviews and deciding what elements to track, I began to ask questions that I was hoping the data would be able to answer. Some initial questions I had were: Were there more bad memories than good? Or, given the circumstances, were there any good memories? In terms of percentage, which gender had more or less than the other of good or bad experiences? What were the age ranges of the prisoners? Where were the majority of the inmates deported to? Where does most of the violence and death happen?

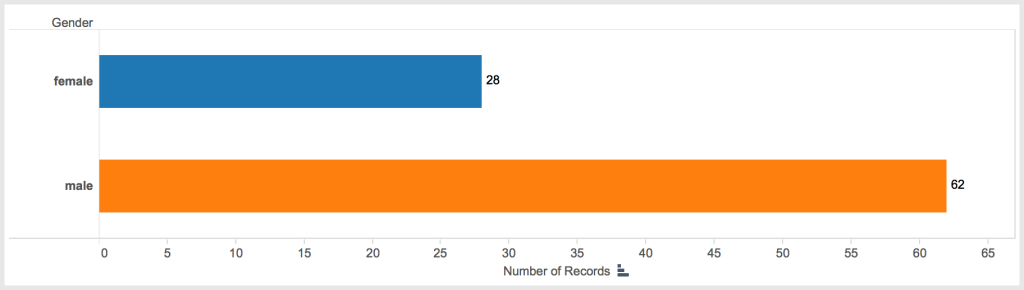

The final question seemed to have the most potential of being answered once I started going through the data to pull out events. I was also able to find that there were indeed good experiences had in the concentration camp. Only after I gathered the data and began to try different ways of graphing and mapping the data did more questions arise. Most surprising were the number of gender based questions that arose from looking at the data. Some of these questions included the following: Which prisoner had the greatest number of events? Since the number of male and female interviews were comparable (6 female and 8 male), which gender had the greater number of events and why? Was one gender apt to have more experiences with certain events than the other?

Other location-based questions arose as well. Although seemingly obvious, where did the majority of work related, violence, and death events happen? Which location had the most events? I was also interested in seeing what patterns or information stood out that was not anticipated.

The data points come from an original pool of 25 transcripts of interviews or other written accounts by survivors predominantly taken during the 1990s. Only 14 ended up having events that could be used in this study. While most of the accounts contained plenty of spatial references, only 14 had such references while recounting their time at the Porta Westfalica camps. Females accounted for 6 and males for 8 of the accounts used in this study. A total of 90 events were found in the 14 accounts.

I was hoping the accounts would be replete with retellings of events and graphic descriptions of the locations where they happened. It would have been great if the survivors were able to describe in detail where they were standing at any given point and had a plethora of events to recount. In reality, the events were much more general and quite vague. Instead of someone describing where exactly in the camp or tunnel they were standing when an event of violence happened, the event was reported more generally; an act of violence happened. For example Tadeusz Kaminski, an 18 year old Polish prisoner in Lerbeck reported that “the camp elder was a German, a sadist without any feeling. Even early in the morning before roll call he would beat the prisoners without mercy. He had a riding crop always with him and would beat as the feeling came.” No specific location is given, just that violence would happen.

A number of limitations of the data should be addressed. First is the limited number of accounts used in the study. Fourteen is admittedly a small number compared to the 2,970 prisoners at the three camps, and therefore all interpretations and conclusions are given in light of a decided lack of representation. Nevertheless, the results that do come from the limited data are instructional and can, arguably, be reflective of the larger number of experiences at the camps.

Second, a number of the accounts were taken from legal depositions or questionnaires where the intent was to show the brutality and inhumanity suffered at the camp. While these accounts may have a tendency to skew the resulting events towards the violent and negative, it can rightly be argued that due to the nature of the camps the overwhelming experiences would be that of violence, death and work.

Third, in some cases I may have been more general and forgiving as to what constituted an event than I was for other accounts. This was not a conscious choice, but is rather an acknowledgement of human error.

Limiting the events to their time in Porta Westfalica severely truncated the experiences of the survivors. Generally, only a third or less of the entire account was about the survivor’s time in the Porta Westfalica camp.

Lastly, the locations of the events were not specific enough to generate a unique latitude and longitude coordinate. Locations were given one of five sets of coordinates that correspond to the Barkhausen camp (as the barracks, sickbay, roll call and bathroom), the tunnel entrance on Jakobsberg (as the worksite for Barkhausen), Lerbeck (which contained all locations), the approximate location of the Hausberge camp (as the barracks, sickbay, roll call and bathroom locations), and the top of the Jakobsberg as the worksite for Hausberge.

I began the process of recording events by making a list of locations and events that I thought would show up in the accounts. My initial list of locations included bathroom, barrack, roll call, worksite, and sickbay; and events like food, work, sleep, life, hygiene, violence, good, death, and sick. The final list of locations and events did not change much. In most cases, determining an event was pretty straightforward. For example, Eva Gescheid frankly described, “we possessed no shoes.” That describes an aspect of life, so easily fits in the life event. The location is less clear. If this is to mean that they had no shoes at all, period, their whole time in the Hausberge camp and adjacent worksite under the mountain, then this event could apply to all locations. In the instances of avocation, food, life and sleep events, I placed all of these in the ‘barracks’ location.

Sometimes the event and location are clear, as is the description of a death retold by Anton Daniel Cornelis van Eijk, a Danish prisoner of war at Lerbeck. “I sat in Lerbeck for six months, and in these six months, so far as I know, two people died.” He then recounts the story of a young Polish man, 28-30 yrs old, who was hanged because he called a camp elder (Lagerältester) a communist. A few prisoners, perhaps Russians, helped with the hanging. Apparently he was not completely dead when they finished, so he was taken to the sick bay where he was given an injection of gasoline which caused him to die. Here both the location and the event are known.

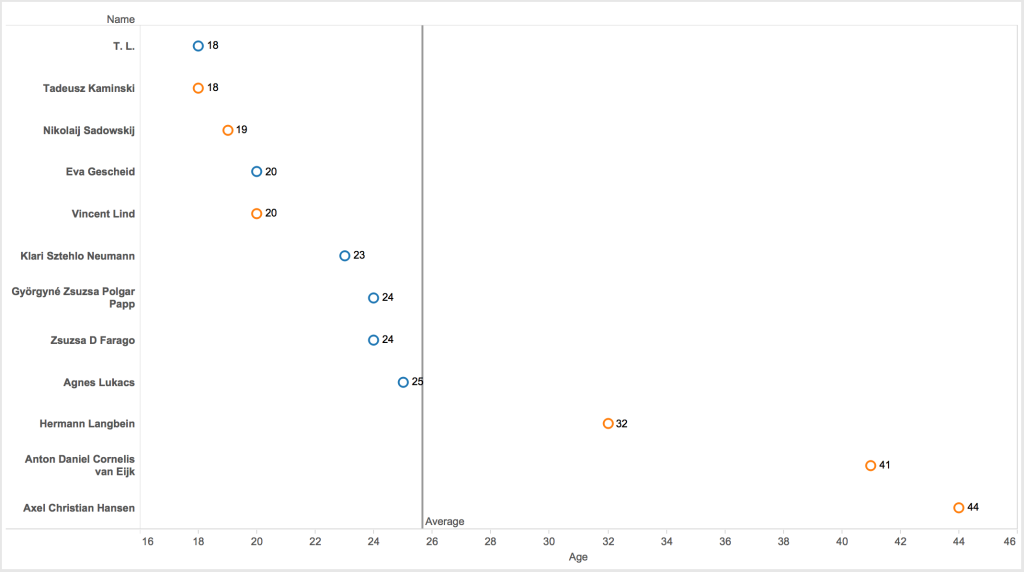

In looking at the data, a number of interesting patterns arise, answering many of our questions from above regarding gender. As noted, only 14 interview accounts out of 24 held information that made it into the study. Again, that’s not to say that the other account did not hold important and interesting data, but they did not recount any experiences that related to Porta Westfalica specifically. The number of interviews ended up being pretty evenly split with six female accounts and eight male accounts. This is rather interesting as there were nearly twice as many male prisoners (1,970) as there were female (1,000). Unexpectedly, the number of accounts from the Barkhausen camp (4) is equal to the number from Lerbeck (also 4). With nearly three times as many inmates at Barkhausen (1,300) as at Lerbeck (500), one would think more accounts would come from Barkhausen. Again this points to the limitations of the study, in that a proportionally representative number of accounts from Barkhausen were not available. The average age of the survivors at the time of internment was 25.5 years of age. Two survivors, Dmitrij Iwanowitsch Zwagorskij and Pierre Lecomte did not have enough data to determine their age at the time.

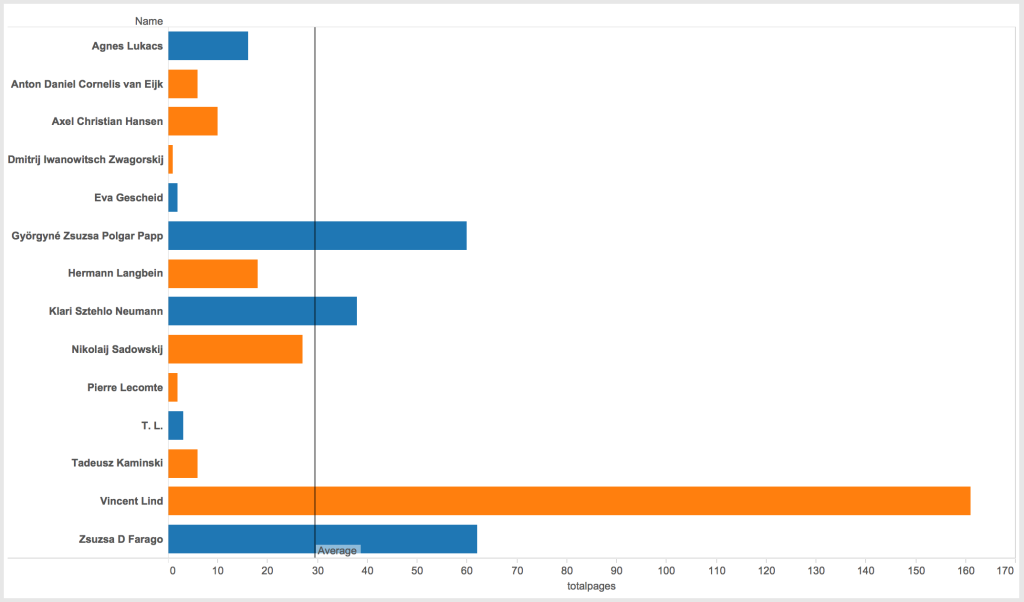

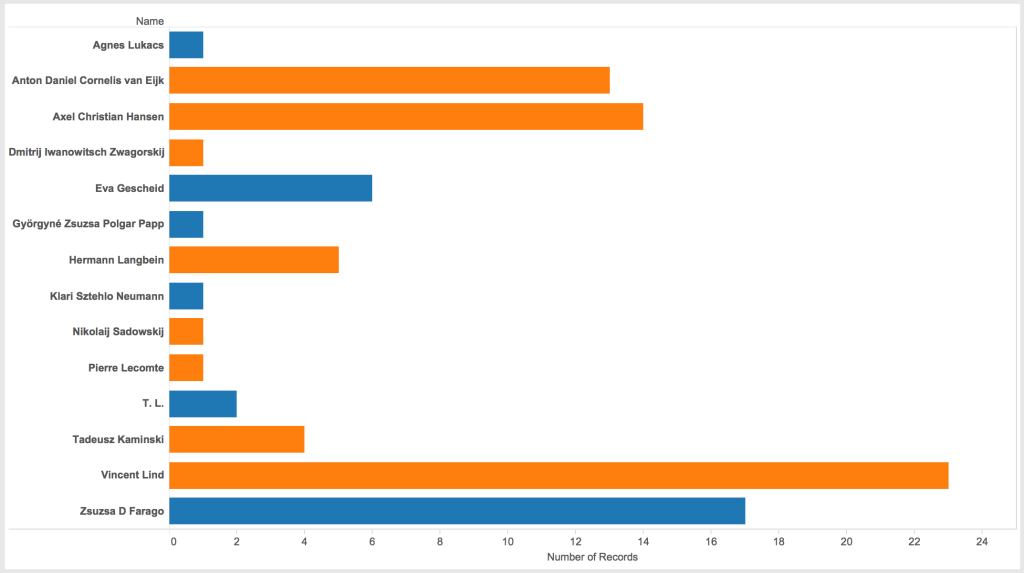

The total number of pages in each survivor’s account is also telling. Males totaled 229 pages of accounts, while females totaled 181 pages. Each survivor averaged 30 pages of interview transcript, although that number is a bit misleading. Only three individuals actually surpassed 30 pages of interview, three women and one man. Vincent Lind, a 20 year old political prisoner from Denmark, accounts for half of the men’s page count at 161, and by far the most pages of any survivor in the study. Zsusza D Fargo and Györgyné Zsuzsa Polgar Papp, both 24 year old Jewish women from Hungary, had 62 and 60 pages respectively, and Klari Sztehlo Neumann, a 23 year old Jewish woman from Hungary was the final survivor over the average with 38 pages.

Comparing total page count with the number of events in the study is also enlightening and somewhat counter intuitive. While Vincent Lind and Zsuzsa D. Farago do indeed have the most number of events represented in the study, Zsuzsa Papp, who had the second most total number of pages, only provided one event to the study. Likewise, Axel Christian Hansen, a 44 year old political prisoner from Denmark, and Anton Daniel Cornelis van Eijk, a 41 year old prisoner of war from Denmark, each contributed 14 and 13 events respectively, while only having 10 and 6 pages of account respectively. This simply shows that the number of pages in the account do not necessarily predict the number of events reported.

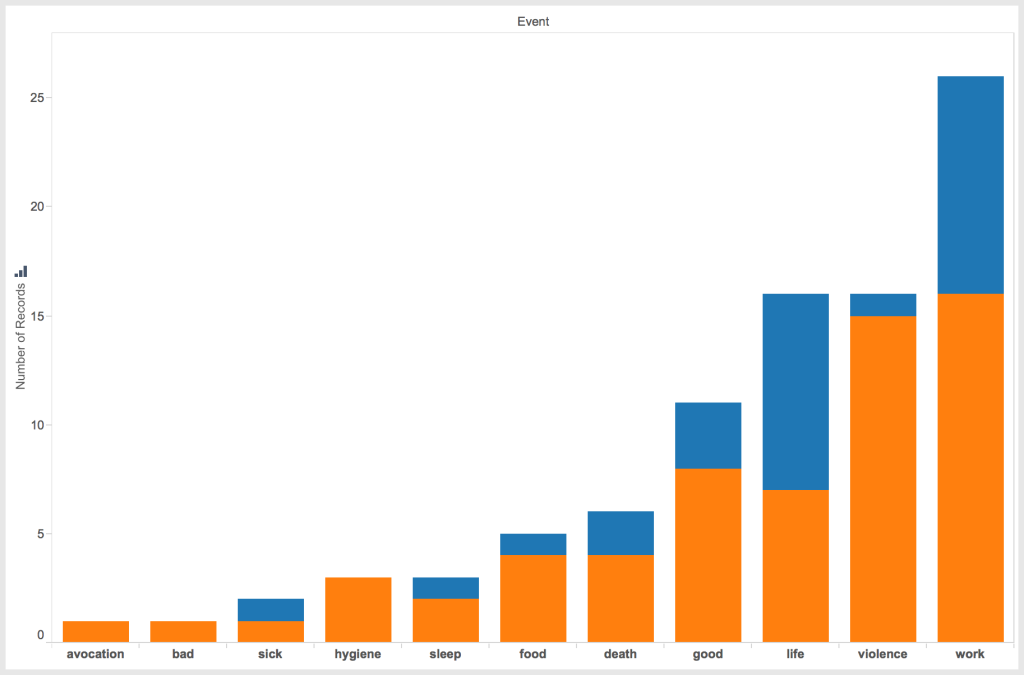

Looking at the events related by gender also uncovers an interesting dichotomy. While males had at least one record in each event, the female accounts mainly centered around three events: work, life and good experiences.

According to the few accounts available, women spoke predominantly about life in the camp, talked about the work they were forced to accomplish, and related a few good experiences. Interestingly, life experiences only had one less than work experiences, 9 and 10 respectively. This seems to indicate the women were more focused on the work and living conditions while at Porta Westfalica. For the women, only one instance of violence was recorded.

As anticipated, men focused their accounts mainly on work and violent experiences, followed by good and life experiences. Also as expected, 51 events—over half the total number of events—speak of negative experiences, with surprising 11 instances of good events happening. Surprisingly, there were not as many accounts of death as expected. With a higher percentage rate of deaths than the parent camp of Neuengamme, I expected there to be more death events in the accounts than was represented. Vincent Lind and Anton Daniel Cornelis van Eijk provide the only male accounts of death, and Klari Sztehlo Neumann and Zsuzsa Farago provide the two accounts of female death in the Hausberge camp.

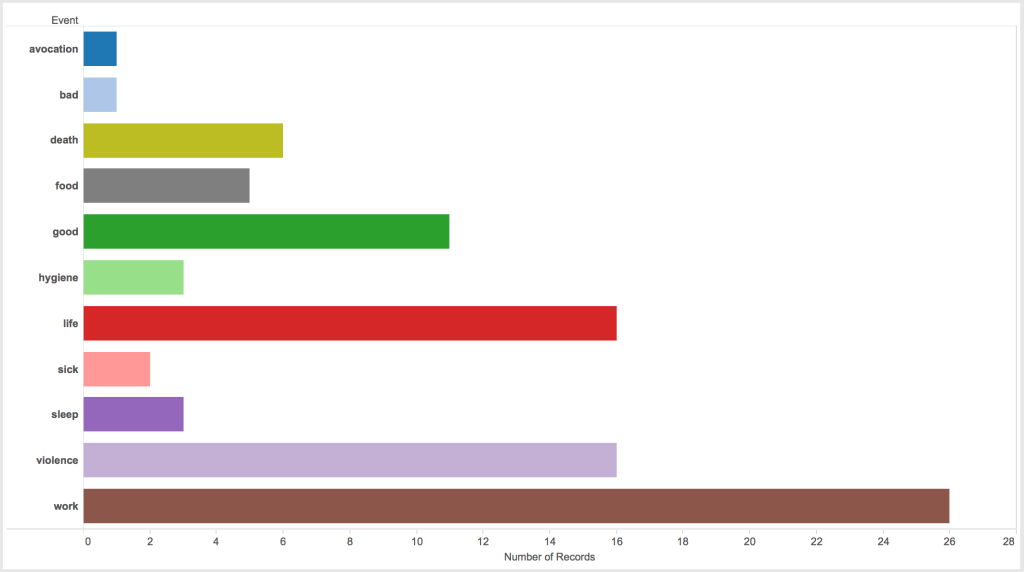

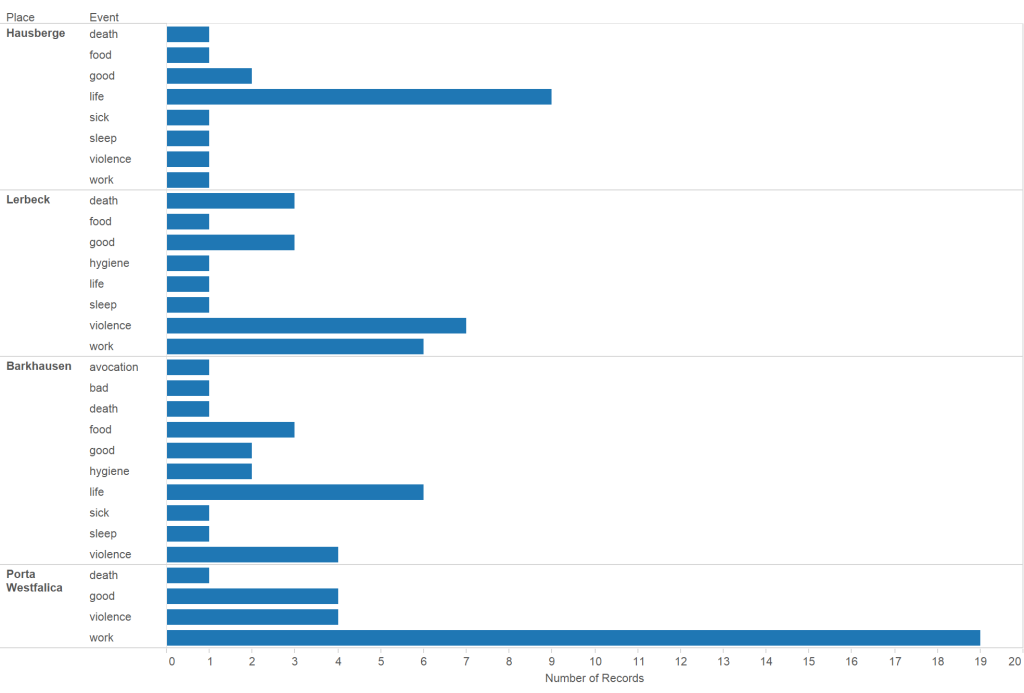

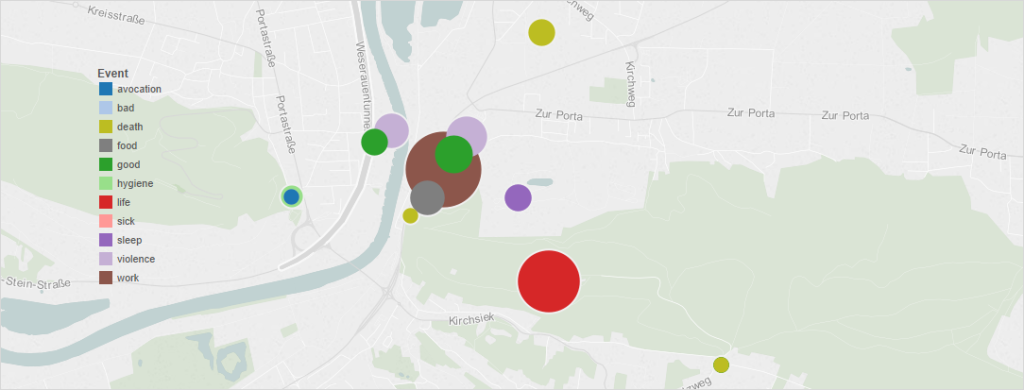

Turning to spatial representations of the data show an equal number of interesting patterns. Work events are the most numerous (26), followed by violence and life events (16 each), good experiences (11), and a surprisingly small number of death events (6). Not surprisingly, at the three labor camps, work events are the most numerous.

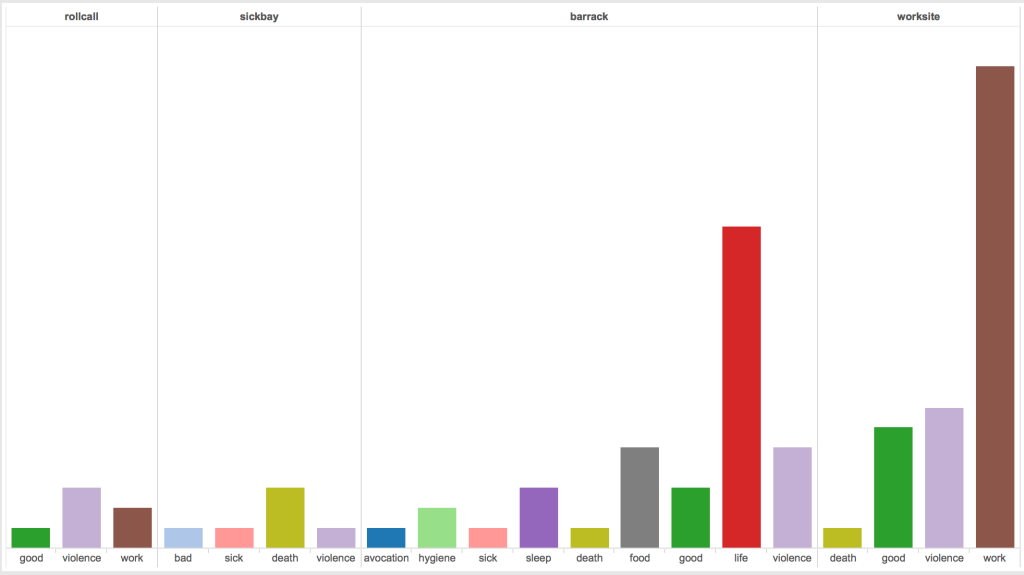

Placing these events where they happened provides more insight. As one might expect, most of the work events happened at the work location. Two exceptions are more related to placing events that are really roll call experiences, rather than work experiences in the the work event category due to lack of a roll call event category.

One of the main questions I had was where did the violence happen. I speculated that most violence occurred near the camp rather than at the work site, in that the SS guards would rather their prisoners work and therefore refrain from violent actions. This assumption assumes that most violent actions came from prisoner guards, but in actuality, violence most often came from fellow prisoners, specifically those with some position like the Lagerältester. Indeed, all seven accounts of violence in the work place came from fellow prisoners. Only two cases of violence at the barracks where perpetrated by camp guards. All three violent events during roll call were carried out by SS guards.

An almost equal number of good experiences as violent experiences at the worksite, and to a lesser extent the barracks. The surprising number of good experiences come from three individuals, some describing the beauty of the landscape, some describing positive interactions with other inmates or civilian laborers, or even a positive interaction with a Gestapo officer.

Perhaps obvious, only negative events happened in the sickbay; three deaths, and one each of violence, sick and bad.

The barracks had the most number of different events, most likely allowing to the barracks being the only other place rather than the worksite where the inmates were allowed to go. At the work site, as seen in the graphs, was mostly concentrated on working. The barracks allowed for a larger variety of action.

Looking at the different camps also shows patterns. Lerbeck had almost double the number of violence than either Barkhausen or Porta Westfalica (worksite), possibly because Lerbeck included living and working conditions, but had less than half as many accounts of work than the work site at Jakobsberg.

Attempts were made at mapping the various events and the location, but due to the small number of locations, the maps do not reveal much more than the graphs.

Data and graphs are freely available and searchable at https://public.tableau.com/profile/ammon.shepherd#!/

A further spatial study arose while reading through the interview accounts. Central to all remembrances was the complete circle the survivors made in terms of their journey; from initial confinement to internment and transportation to various camps, and the journey back home. The next spatial project will use Omeka and Neatline to create an interactive journey of several survivors. As the narrative of the journey is told, the locations will be displayed on the map, and visitors will be able to follow along on the map as well as with the narrative.

The project will be hosted at http://nazitunnels.org

One final thought and caution to keep in mind when doing spatial projects with such sensitive and emotional data is that plotting and graphing the data can abstract the humanity from the survivors, as they become dots on a map rather than people. Care must be taken to keep the humanity in these spatial humanities studies.

One way to do that is to always reference the names and use examples of their experiences.

[1] Jodie M. Plumert and Alycia M. Hund, “The Development of Memory for Location: What Role Do Spatial Prototypes Play?,” Child Development 72, no. 2 (March 1, 2001): 370–84, 370.

[2] David C. Rubin, “A Basic-Systems Approach to Autobiographical Memory,” Current Directions in Psychological Science 14, no. 2 (April 1, 2005): 79-83, 80.